Prof. Jaap E. Doek, the chairperson of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child since May 2001, is a professor of law in Amsterdam and had been the dean of the Law faculty at the Vrije Universiteit from 1988 to 1992. Currently he is a deputy justice in the Court of Appeal of Amsterdam and has been a juvenile court court judge in the district court of Alkmaar and the Hague (1978 - 1985) SHARON KAM was briefed on his mission and concerns recently.

theSun: What is the work of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child?

As the chair of the UN committee on the rights of the child, we have to spend three months for sessions of the committee. Those are the meetings where we discuss with delegations of nations, the reports that they have submitted to the committee, on the implementation of the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC). They have to report every five years.

As a university professor, I opted for an early retirement that allowed me to do this. The interesting and kind of inspiring part of it is you always meet with people even if it is in North Korea or Myanmar, you meet with people who are really committed to children - their health, education, protection from years of violence. So you don't need to sell a vacuum cleaner that nobody wants to buy as you are already selling something they are already committed to.

So at those discussions with state delegations, we encourage and explain to them what we expect them to do under the CRC and to encourage them to submit their reports.

The last time I was here, I encouraged the Malaysian government to submit its first report so I had meetings with the Attorney-General and officers from the Ministry of Women and Family Development recently to discuss the current state of Malaysia's report. Although there was an optimistic expectation that it could be submitted last November 2005, they still have not submitted it. But I was told that it is about to be submitted to cabinet so that looks good.

We have 192 states that report to the committee. Most of the 192 state parties have submitted their reports for the first time, there are only couple of them left. We will meet Samoa in September and I was in Fiji trying to urge the other states in the Pacific who have not reported yet. Malaysia is the other one, (along with) Timor Leste and Afghanistan. So we are down to about seven countries out of the 192 that have not submitted but I am confident that not only Malaysia but some other Pacific islands will submit their report in the coming months.

After the report has been processed by the committee, the end result is the recommendations to the government for further action for the next five years. The committee is one of seven human rights committees. These committees are in charge of monitoring what state parties do in terms of their performance. One of the things the committee also does is to organise so-called days of general discussions every year in September.

The days in 2000 and 2001 were on violence against children in various settings so it was not limited to families but also to schools, prisons and other settings. In juvenile justice, a lot of juvenile delinquents are subject to all kinds of maltreatment. We do have countries that still use corporal or physical punishment as a form of punishment in the juvenile justice system. One of the recommendations that came out of those two days of discussions were for the general assembly to undertake a study on violence against children. To do that we acquired an international expert from Brazil. The whole operation is funded by donor countries.

Questionnaires have been sent to all state parties around the world - and close to 130 countries had responded, which is an unprecedented response not only in the UN but for all other research that you do. If you sent out a questionnaire that has to be filled up, your response is at best 20-25%. If the number is small, then it is not representative of the rest but if you have 130 out of 192 then it is kind of representative of all of the 192. So the responses are being analysed and compiled by the secretariat into a report.

The second feature of the study is the regional consultations - very important process because the study should not be just a desk operation or questionnaire but we must go out, meet with NGOs, government representatives, meet with UN agencies particularly Unicef and also others like WHO, International Labour Organisation to discuss on violence against children in the various settings. And in this study, the settings are family, school, juvenile justice, the community and institutions like children homes. The regional consultations resulted in recommendations and a report which included other consultations and other sources of information. The study is expected to be completed by the end of this year.

What will happen is two publications - a book which will elaborate on the settings I mentioned and there is the report - the key document that goes to the UN general assembly and it has to be limited to 35 pages according to the rules of the UN, don't ask me why.

There will be recommendations that may run into difficulties of being acceptable by state parties, the most controversial one is the recommendation on corporal punishment. We are of the opinion that corporal punishment should be prohibited. Some people associate prohibition for children below 18 but that is not the case. Even in this country where you still have caning as a punishment for juvenile delinquents, I think the committee on the human rights of the child is of the opinion that it is not acceptable under the convention. There is a growing number of states that do have prohibition of corporal punishment in schools. The problem of violence is also between students like the issue of bullying which is an increasing problem in quite a number of countries.

Q: What do you mean by the way parents discipline the child?

We are not against disciplining, of course. Disciplining is part of your upbringing of children but we are against using physical forms of violence in disciplining the child.

The same goes for corporal punishment in the criminal justice system. You may think that it does help but we are saying that even if it did help, it is a violation of the human dignity. We have other ways of punishing, or correcting. It is difficult to make sure parents do not continue punishing their children physically. This requires proper educational campaigns, information, parenting classes to convey the message that it is the wrong thing to do. And there are countries which do have prohibitions on corporal punishment by parents in the family. It is really changing the attitude of parents. But studies show there is a change in habit and perception of the use of physical force in the upbringing of children. There is a clear reduction of this form of physical abuse in the family.

In Sweden, you will find a remarkably low level of children that has been subjected to physical punishment but it is impossible to achieve 100% physical punishment-free society, but you can work on it and bring it down to a very low level. The anomaly is you get all those people saying, "I was a child and my father had beaten me but see here I am, I am the Prime Minister of this country." My response is, you are PM not because you have been physically punished by your father but because you had the drive and ambition to be the PM of your country. So that type of argument is not really convincing.

The committee is preparing a document which explains in detail its position on corporal punishment in all kinds of settings. We do have a lot of scientific evidence that tells you that there is a serious risk of increase of the use of physical violence when it starts with the kind of slapping that is in normal upbringing as it may raise to other levels. But there are also some evidence in some studies that indicated that it is OK to punish your children. The committee's position is that even if you can prove that it helps, it is still wrong because it is a violation of human dignity and of physical and mental integrity of children and it is ultimately the indicator of your respect for children as life forms.

It is really embarrassing I think for the Supreme Court in Canada while presiding on a case of corporal punishment to decide that it is not against the constitution. And it went on to explain what forms of violence against children constitute reasonable chastisement. They said if you beat the child aged 3-12, and if you do not use an instrument, and you do not hit the child on the head, that is reasonable chastisement. Why between 3 and 12, I don't know. Without an instrument, I can understand, but it still sends the wrong message. Apparently a child can be subject to physical force because the child is somebody who needs to be disciplined.

And you do not believe how hot the debate can be on corporal punishment. As soon as you say you prohibit corporal punishment, you are run over by journalists, TV, radio, they all want you to explain why it should be prohibited. In the 70s, there was a bumper sticker that said, 'People are not for beating and children are people too'. That is the basic rule. Sometimes you can use force to protect the child. For instance, when the child is beating another, you need to use force to constrain the child or when the child is crossing the road dangerously, you would need force to get him out of the way. But that is not the issue. The issue is, you want to correct the child, so you call the child, come here and then you slap the child. That is not respect for human rights so that is what we are trying to convey.

Is violence the main violation against children?

Yes, we are not just focusing on corporal punishment. If you look at what happens in certain institutions for instance, not only juvenile correction centres but also children's homes, orphanages, you can find reports of abuse where officials working in those institutions are using terrible forms of violence beyond merely constraining those inmates that are violent.

I still remember one story where they cut off the teeth of an inmate and that is only a small part of the torture that was going on. In a lot of countries, there is very limited control from the outside on what happens inside those institutions. From reports, we know the problem is very widespread in a lot of countries.

You have to have a real strong independent monitoring system like a Commission of Human Rights. One of the things an independent commission should have is the clout and the authority to visit all kinds of institutions and do that unannounced. And they must have the right to talk to those inmates of those institutions. One example is the Guantanamo Bay detainees. The US said, well, the Human Rights Commission can visit Guantanamo Bay but they cannot talk to the people that are being held there. Well, we are not going there to look at the building to see how the structures are or whether they have water and electricity. No,no,no, we want to know more about the treatment. Of course if we are there, the inmates will be very decently treated. But we need to talk to the inmates and we want to have that information first hand from them. But it all has to be confidential, that is very important.

But whether it is a children's, juvenile or adult institution, they have to have an independent person outside of their institutions, that they can complain to, someone outside that has the power to pursue the issue that has been brought to their attention and that person must have the authority to make recommendations to the director of the institution.

Sometimes (it may be) trivial things like food for instance. Let's say chips which are far beyond the date of consumption. You may think that is trivial to complain about but for those kids, that is important. And violence in institutions. For children they are the most vulnerable because they often do not have family that is interested. They are completely left on their own, very insecure. They do not know what will happen today or the day after tomorrow.

Why do you think some people treat children this way?

It has to come from a deeply-rooted attitude towards children as a kind of property and a person that has not yet achieved full development and therefore needs a lot of correction, guidance, instruction. The well-known religious defence of corporal punishment is spare the rod and spoil the child and that is apparently a deeply-rooted belief which says the child needs to be corrected and this is somebody that is small enough to be corrected in a very forceful manner.

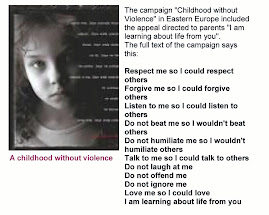

For instance, why did the Supreme Court of Canada state that reasonable chastisement (is allowed) between 3 and 12? Why does it end at 12? I know why, because at 13 they can kick you back. I think the only way to change that attitude is to work on the message that children are human beings and therefore should be respected and that respect for human rights includes respect for human dignity and mental and physical integrity. That should lead to the conclusion that we do not accept violence against children under any circumstances. We do understand that parents sometimes in a desperate act to correct the child, may hit the child. But we do have enough information to teach parents how to do it in a non-violent manner. A lot of documentaries and instructions and videos ...

Maybe that takes too long a time to get results.

Well it takes time but violence against children is not acceptable. You understand the difficulties parents face but still you have to continue telling them to work towards a situation where you do not rely on violence in the upbringing of your children. And there is enough information to do that. There can be a long term campaign that can start in secondary schools, that can start in all kinds of classes for parents, for expectant parents. Since you can produce children, it is also good to learn how to bring them up. You see in pictures and advertisements all those beautiful images of parenthood where children always look good and never cry. We should also show problems when dealing with children and come up with tips on how to deal with some of those issues. You could have brochures on how to deal with your children in the supermarket and put them along supermarket alleys where parents can pick them up so you know how to deal with a child who wants a candy bar he should not have.

What other violence against children is the UN concerned about?

Violence in schools, because despite some of the official prohibition of violence in schools, a number of teachers continue to hit children and we really need to teach teachers how not to take violence as a form of discipline. If teachers hit students, why won't students hit their peers? Bullying is another issue. We hear all sorts of sad stories of children who were the subject of bullying which makes school a very unpleasant place when it should be a joyful meeting place for children.

There are also special issues of children in refugee camps. Girls are very vulnerable and children in armed conflict situations where women are raped and as a result we have a number of street children who were not the product of any consensual sex. And there is the whole area of sexual exploitation - full of violence and that constitutes abduction, trafficking, but a lot of attention has been given to this in this part of the world. If you look at the region here, South East Asia, that had been known for sexual exploitation, where you get a lot of visitors from abroad who came with the idea that they could easily get a young girl for sexual purposes, I think there is less and less likelihood now that they will go scot-free. A lot of measures have been taken to make it clear that it is a very risky business to try to get young children for sexual gratification even if it is not done by physical force, by money or something else.

Are there any specific problems in Malaysia that you are concerned about?

Well, the juvenile justice is a part that really needs a lot of discussion to further improve it. Caning as a form of punishment is not something the committee would ever accept. I cannot tell you all the recommendations the committee would make but one is for sure - no caning for juvenile delinquents. Treating some 18-year-olds as adults is another one. Quality of detention, lack of alternative measures like community service and others, it is not easy to do it well but I think it can be done. There should be a very specific plan of action to really move towards a system of dealing with juvenile delinquents which is in accordance with human rights. There is quite a lot of experience, knowledge and information to support the government in this. But there are a couple of good things -the performance of Malaysia in education is well above the average, same applies for health, infant mortality is far below everybody else in this region, pre-school education is really exemplary for the rest of the region. But that is not unusual for most states. In a lot of Islamic countries, I don't know for Malaysia yet, but there is a growing problem among Muslim countries of children born out of wedlock. There are situations where women kill themselves because the child and they are not accepted. They cannot take care of the child and the child is a marginalised person. Extended families don't want to take care of the child, so you really have to put the child up for adoption. And of course the fathers are the free-flying guys, they are not made accountable. They do not pay child support and are not held equally responsible for the child.

Why is Malaysia taking such a long time to submit their first report to the committee?

In Malaysia, we have discussed at length with the Attorney-General the long list of reservations that the country has. If you have ratified the Convention, you can make reservations. Reservations means that you intend to implement the Convention but not for that article, or this article maybe because it is not in accordance with the national law, or whatever law. So Malaysia has a long list of reservations, some of which I think are completely unnecessary. But I think they are going to withdraw most of them. For example, according to Article 28 of the CRC, the state must ensure free, compulsory, primary education. But because they do not meet ÒfreeÓ they make a reservation against Article 28. It is not because they do not want to have free education but, they say, since we do not comply yet, just as a precaution, we make a reservation and as soon as we have real free education, then we withdraw. I told them this is not what most countries do, most countries do not have real free primary education. A lot of them do have to pay for uniforms, books, transport but they do not make a reservation because a reservation also psychologically creates the wrong perception that the Malaysian government does not want to have free primary education. So that is an example of how the Malaysian government is operating those reservations so most of these reservations can be withdrawn. Then there is the sensitive issue of freedom of religion. That is not unusual for most countries with strong Islamic law to have reservations on Article 14. Other countries like Indonesia, the Arab world, they all have reservations on Article 14. So you have to keep in mind that state parties can make reservations and they have the right to make reservations. So it is not something that you cannot do but the committee is of the opinion that you should have as few reservations as possible, preferably no reservations as that would be the full-blown commitment to the CRC.

For countries which have ratified the Convention, what is their main barrier in fully committing themselves to the Convention?

Lack of human and financial resources - poverty. Poverty is a very serious problem and has been identified by the (UN) secretary-general as the main obstacle to the full implementation of children's rights. That does not mean that poverty is a justification for doing nothing. Quite a number of things under the Convention can be done with small amounts of money. For instance, child participation is something the committee and the convention very much promotes, where children can have a say in things that affect them such as school regulations. It does not cost a lot of money but it does cost a change in attitude and sometimes that is much more difficult. The corporal punishment issue is one of them. Where it cost money would be for education and healthcare and we see the budget allocations for healthcare and education in some governments to be far below international standards. The UN says 6% of the Gross Domestic Product should be for education but a lot of countries just cannot afford it and that is partly due to the debt interest payment and repayment which accounts for 30-40% of their national budget. So the committee also recommends that countries if they do get any debt relief, to consider that part of money that they have saved in their next budget to spend on children's issues Ð on education, on healthcare of mother and children and social services and not spend it on all kinds of very prestigious projects like a beautiful bridge that nobody needs but has the name of the PM on it. We see over the last 10-15 years there has been an amazing increase in awareness. The World Bank 15 years ago, did not talk about children's rights at all. Now, they do talk a little bit on children's rights, and they do have child labour programmes, so even those institutions that were not well known for their interest in children's rights are becoming more so. It is not going to show any kind of very significant changes over a short period of time but the whole exercise is also to increase awareness, to identify children who are in trouble because they are not protected, they are abused. The impact of the CRC is also to make it possible to protect children, to combat child abuse more effectively.

No comments:

Post a Comment